Mention of the word museum often brings to mind a place in which old, dusty, static objects – albeit valuable ones – are preserved in rows of glass boxes. But history is not a static phenomenon; it is constantly interpreted and reinterpreted in different forms: not only novels and records, but also exhibitions, video games, audiovisual works and so on.

So, what does history look like in a museum? A few questions are worth considering. Could a museum exhibition count as an adaptation? Museum professionals variously see themselves as collectors, scholar-researchers, educators, conservators, money-making entertainers and consultants with stakeholders in a community. But are they also adapters? A museum exhibition takes material objects from the past and recontextualizes them within a historical narrative. But does the audience experience it as such – that is, in a palimpsestic way?

Academic studies of adaptation generally identify three modes of engagement with a text or object: telling, showing and interacting.1 This framework also applies to how we look at history, particularly in museums. Both showing and interacting are involved when museum visitors explore the history presented in the objects and images that comprise the exhibits, and reconstruct that history in their minds.

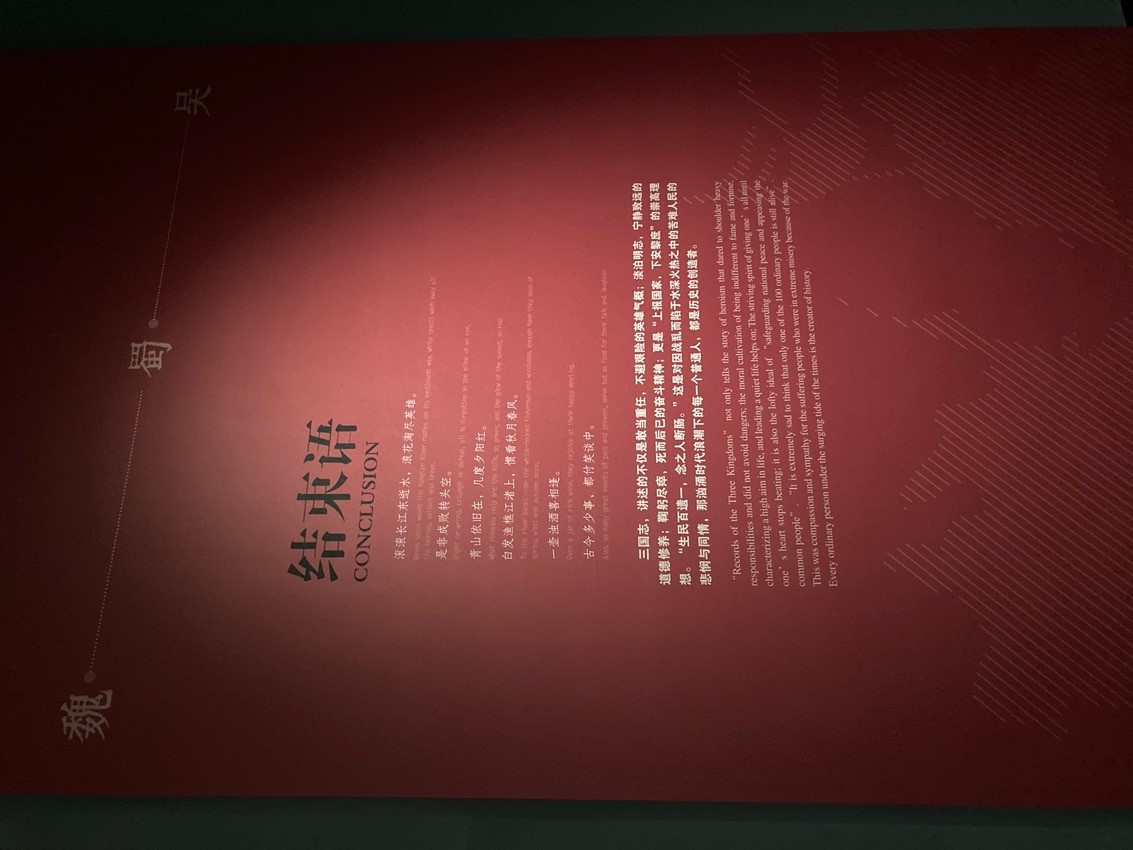

A few weeks ago, I was passing by a local history museum and was attracted by a poster outside advertising a special exhibition on Records of the Three Kingdoms, a classical Chinese historical text. Mostly out of my own research interest, I decided to go in.

Apart from the range of objects from the Three Kingdoms period on display in the exhibition, as well as the archived printed books and paintings related to the period, I was also impressed by its introduction to the history: a short video presenting clips of key parts from the 1994 Three Kingdoms TV series, presented on a screen in the corridor connecting different sections of the exhibition. This video brought back memories of the good old days when I was a child and watched the series every winter and summer vacation. Being very faithful to the novel on which it is based – Luo Guanzhong’s San Guo Yan Yi (Romance of the Three Kingdoms) – it is a very popular adapted work, with 500 billion views on Bilibili, a popular streaming website in China, as of June 2020. The use of footage from this TV series in the exhibition therefore brought the history and the items on display much closer to the visitors (myself included).

Aside from this display, and the larger screen presenting beautiful landscape videos of various small local towns as they would have appeared in the Three Kingdoms period, there were a number of interactive exhibits set up throughout the museum. During my tour, I noticed quite a lot of children playing the fishing games, a good way to learn about the changes in the fishing industry around Taihu Lake, while other visitors were using texture machines to explore the history of texture-making south of the Long River and the delicate craftsmanship of Suzhou embroidery.

As Hyuk-Chan Kwon has pointed out in his discussion of Three Kingdoms adaptations, ‘The reader often attempts to accommodate new Three Kingdoms revisions enhanced with more liberated and imaginative interpretations and re-creations in terms of translations or adaptations of the novel, console games, Internet role-playing games, cartoons, and animations’.2 Museums can be added to this list of ‘liberated and imaginative interpretations’, weaving the intertextuality between historical novels, records, antiques and audiovisual works into the visiting process. The cultural world presented in the museum through the adaptation and reshaping of the original history resonates with the world of the Three Kingdoms period in the visitor’s mind.

In addition to all this, the museum organized a programme of events based around the Three Kingdoms exhibition, including educational activities, academic lectures and in particular the ‘Night Reading of the Three Kingdoms’ reading salon, which delved into the details of society, poetry, the humanities and other aspects of cultural life in the Three Kingdoms period. I attended one of these salons, and found it absolutely fantastic to be able to continue a journey I’d started in the pages of books in a series of evening talks along a riverbank, hearing a panoply of voices from various corners of society interpreting the historical period and characters of the novel in a host of different ways. The museum even released a special New Year’s edition of Romance of the Three Kingdoms in a modern, vernacular style for the audience to read for free.

Experts also got involved in both engaging with and publicizing the exhibition. On 3 March, Yi Zhongtian, a scholar studying the Three Kingdoms history and related literary works and well known in China for his excellent storytelling on the popular TV show Bai Jia Jiang Tan (Lecture Room), made a visit to the museum, and the Three Kingdoms exhibition in particular. Yi praised the collections of cultural relics from the Three Kingdoms period, taking particular interest in the pottery buildings from the late Han Dynasty, as well as the repeating crossbow machine. Though his views on this period are somewhat controversial in academia, his visit did attract more attention to the exhibition and, again, brought this display of antiquities closer to modern people and society.

As public spaces, in short, museums offer a way of thinking about the variety of responses that can exist in society to an established story or historical narrative. The integration of the showing and interacting modes of engagement position the adaptations of history presented in museums specifically as (re)interpretations and (re)creations. Arguably, therefore, museums represent an extended interpretive and creative engagement with the past.

- See, for example, Linda Hutcheon and Siobhan O’Flynn, A Theory of Adaptation, 2nd ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2013). [return]

- Hyuk-Chan Kwon, ‘Historical Novel Revived: The Heyday of Romance of the Three Kingdoms Role-Playing Games’, in Playing with the Past: Digital Games and the Simulation of History, ed. Matthew Wilhelm Kapell and Andrew B. R. Elliott (New York and London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 121–34, 126. [return]